Understanding Personality and its Relationship to School Leadership

Jamie Estes Jamie Estes

|

In recent years, topics in school leadership have filled bookshelves, conference agendas, and magazine pages, including the recent NAIS Trendbook. Issues include generational shifts (boomers retiring), heads’ shortening tenures, and what some see as insufficient preparation of new leaders. Independent schools face more competition and more pressure than ever. The importance of excellent leadership has never been greater. As a search firm, Southern Teachers helps schools see the organizational implications of candidates’ leadership styles. Five years ago, we incorporated personality assessment into the retained search process. Three years ago, we began a series of studies to help schools better understand the power of these assessments.

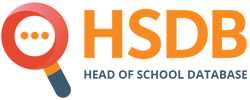

We embarked on these studies to learn about specific personality traits that distinguish strong independent school leaders. A clearer understanding of this group’s norms would make personality assessments more effective in our head search processes. Previously, assessments had helped us learn more about each candidate. Even better would be understanding how each candidate’s personality traits compared to those of independent school leaders in general. A second goal was to inform independent school leaders about concepts in personality science. Many are familiar with assessments such as Myers-Briggs and DiSC in their own self-development, but they are often unaware of an assessment’s broader potential uses. We wanted to introduce a different tool, Hogan Assessments. Founded in robust research, Hogan Assessments offer an effective and versatile tool for the candidate screening and selection process, as well as in a leader’s ongoing personal development. PHASE I – The Hogan Personality Inventory In Phase I, we asked our study participants, 247 sitting heads at independent schools in the Southeast, to take the Hogan Personality Inventory (HPI). Hogan Assessments are among the world’s most widely researched and commonly used personality assessments. Hogan Assessment tools are available in over 40 languages and are used in more than 50 countries by small firms and Fortune 500 global companies. Hogan processes a million assessments each year. Over nine million people have completed them. The HPI is used to predict “bright-side” personality—how people present when they’re at their best. It focuses on a person’s characteristics during social interactions—qualities that can affect a person’s ability to get along with others and to achieve goals. This tool predicts occupational performance by measuring day-to-day personality characteristics that drive behavior. The HPI measures deeply ingrained characteristics that impact a person’s approach to work and interactions with others. The HPI includes seven primary scales:

In the areas of adjustment, prudence, and inquisitive, independent school heads show little difference from the larger population (as reflected in the bars at the 50% level in the chart above). They are no more or less emotionally stable, no more or less conscientious, and no or more less intellectually curious than professionals across industries. They are also very close to the average for sociability, though it is worth noting that only in sociability are they below the global norm. Heads of school, on average, score six points higher than average on learning approach, suggesting that they value traditional learning and the pursuit of understanding as an end in itself a bit more than the general population does.

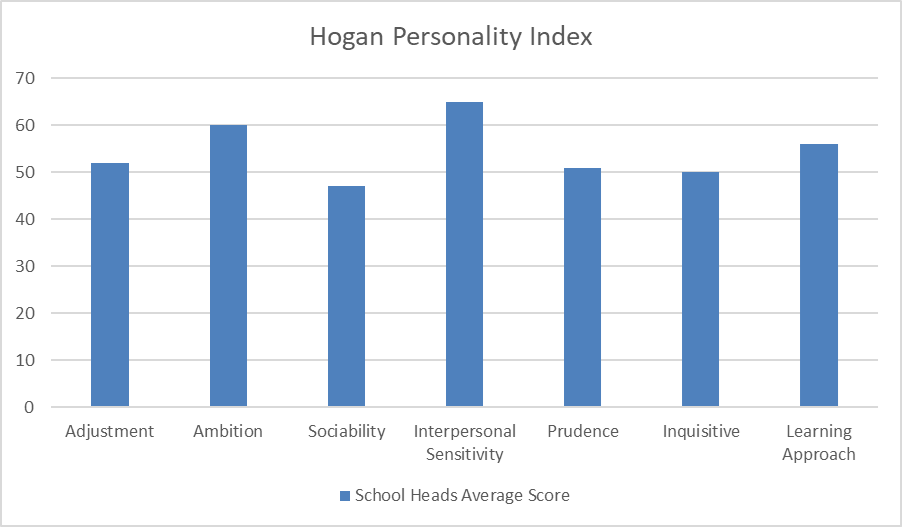

In two areas, independent school heads are outliers. They score almost 10 points higher than most people on ambition and 15 points higher on interpersonal sensitivity. Perhaps these two qualities make someone more likely to become a head of school. They also shed light on what makes being an independent school head so difficult. Ambition is related to one’s desire to get ahead and achieve individual and institutional goals. It is not surprising that people who rise to leadership are more ambitious. Interpersonal sensitivity indicates the desire and ability to get along with others. Building strong relationships is a key to success and advancement in social institutions like schools. However, a leader’s desire to advance his or her career and to achieve organizational goals can conflict with pleasing as many people as possible. Corporate executives score in the 69th percentile for ambition yet below the 50th percentile for interpersonal sensitivity. In the corporate world, getting ahead outweighs getting along. Board members with corporate backgrounds can benefit significantly by seeing this key difference in personality and perspective between the sorts of business professionals they typically encounter and the heads of school they supervise. PHASE II – The Hogan Development Survey Phase I used the Hogan Personality Inventory to examine such “day-to-day” traits and behaviors as emotional stability, ambition, and conscientiousness. Phase II looks at what Hogan calls the “dark side” of personality. The Hogan Development Survey (HDS) provides insight into what people do when they are under stress or feel a loss of control. It describes our “derailers.” Phase I looked at how heads of schools find success. Phase II considers what might get in their way. When we wrote to heads of schools in March 2021, we acknowledged that our study’s timing was apt. Leading a school can be stressful in even the best of times. Occasionally feeling a lack of control comes with the job. The pandemic has brought so much more. Here are some general conclusions Hogan has drawn regarding the HDS:

The HDS includes 11 primary scales of behaviors in the following ranges:

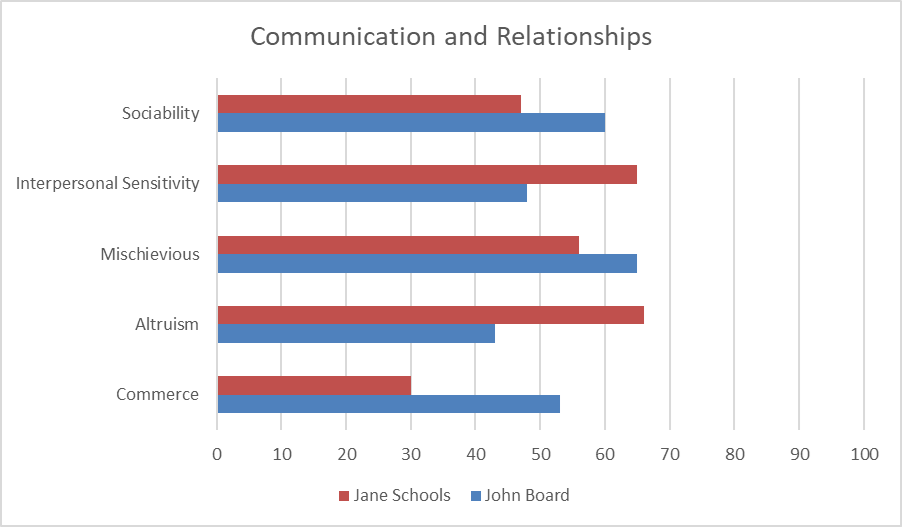

Over 200 heads of schools from 16 states in the South participated in the study. The mean scores in the chart below suggest the “average” results for school heads as a group. These scores do not convey the variability or diversity of individual participants. Larger sample sizes tend to regress to the mean. Thus, it would be very unusual for a group to exhibit scores in the 80th or 90th percentile. Also, it is important to note that the assessment data represent general trends within sample study groups and are not tied to actual on-the-job performance. In all scales, the heads’ average scores are above the global norm. The lowest scale for heads is Skeptical, with an average score of 50.86. On four scales, heads averaged above the 60th percentile: Leisurely (66), Reserved (63), Colorful (61), and Dutiful (61). These behavioral areas call for increased awareness. [Co1] PHASE III – Hogan’s Motives, Values, Preferences Inventory In 2022, Southern Teachers will be conducting the third phase of this study using the Hogan Motives, Values, Preferences Inventory (MVPI) which is designed to serve two important goals. First, the MVPI helps evaluate a person’s “fit” in an organizational culture. Second, the MVPI helps people understand their interest, motives, and drivers. The results will identify what these school leaders enjoy and what kinds of work and environments they will find most satisfying. PULLING IT ALL TOGETHER The real value of Hogan comes when we look at these scales in relation to each other. On the chart above, we have average scores for school leaders and corporate leaders on five of the 28 Hogan scales--sociability and interpersonal sensitivity from the HPI, mischievous from the HDS, and altruism and commerce from the MVPI. For the sake of this discussion, we are using the average MVPI scores for university presidents.

First, imagine that each average score on the slide represents an actual person’s score. The red bars represent the scores of our imagined head of school, Jane Schools. The blue lines are for our corporate board chair, John Board. Now imagine that Jane and John, as head of school and board chair, are having problems. We have asked them to take the Hogan and we want to focus specifically on what the data reveal about their approaches to communication and relationships. When we do this sort of work, we focus on just a few scales from each assessment. We can start by looking at the HPI, where Jane and John are exactly opposite. John is high sociability and low interpersonal sensitivity. He is described as gregarious and charismatic. He loves to work a room. But he can also be very blunt. People know he will speak his mind, and that intimidates some people. Jane, on the other hand, is high interpersonal sensitivity and low sociability. She tends to maintain a smaller group of important relationships. She is friendly to everybody, but some people perceive her as hard to know at first. She attends all school events but never makes a show about it. John wants Jane to be more of a “face of the school,” but Jane values building meaningful relationships one at a time. John wants her to be harder on underperformers, but Jane believes that with time and patience weak performers can become better, and that staff continuity is essential. John and Jane began having problems under the stress of diminishing lower school enrollment when a new competitor school opened nearby. The HDS scale addresses how one operates in times of stress. John is high on the mischievous scale. In his business, when stress ramps up, he tends to be spontaneous, flexible, and impulsive. Jane, on the other hand, is lower on the mischievous scale. She likes to follow set procedures and minimize risks. As they discuss options to address the enrollment issues, John has lots of ideas, some of which are unconventional and make Jane nervous as they may detract from the school’s mission. John believes detraction from the mission is irrelevant if the school no longer exists. Desperate times warrant desperate measures. He uses his personal charm to win board support for his plan. Restrained and muted, Jane feels she is losing influence. From Jane’s perspective, John is ignoring commitments. From John’s perspective, Jane lacks the spirit of adventure necessary to grab opportunities as they arise. At the heart of the disconnect between John and Jane are the differences in what they value most. Their MVPI scores offer insight. Jane scores very high for altruism. She is an excellent listener; she enjoys helping others, promoting staff morale, and fostering open communication. She got into education to give back, and one factor she sees in the enrollment decline is a tightening of financial aid. She does not want their school to serve only those who can pay full tuition, and she has pushed John and the board to allow more discounting to fill empty seats. John, on the other hand, is high on commerce. He works in a world where the number one priority is the bottom line. He pays close attention to budgets and compensation issues. He believes in the school’s altruistic mission, but he’s committed to staying within certain guidelines. John believes discounting tuition to fill seats devalues their product, which is unacceptable and has long-term implications. Jane and John knew they had a problem. The Hogan helped shed light on how they each saw the other. Looking at these five scales offers a useful vocabulary for WHY they see each other the way they do. Schools benefit from having both types of people—like Jane and like John. Understanding different values and perspectives can lead to effective adjustments in practices and improved communication at the highest levels of leadership. It can help schools thrive. Over the past two years, Southern Teachers has posted 16 articles to help schools better understand personality and its relationship to leadership. We believe that by using rigorous personality assessments in the leadership search process, independent schools can identify candidates best suited for their unique cultures and needs, which in turn will enhance a leader’s effectiveness and longevity. More info at https://southernteachers.com/leadership-study. James Estes and Rod Chamberlain, Southern Teachers |